Lubricants: The Unsung Enabler of Smooth PVC Foam Board Production & Quality

2025-12-05

If you've ever walked into a PVC foam board factory, you know that the process is about balance-getting the right heat, pressure stability, material flow smoothly, and turning the raw resin into the uniform, durable boards we use for signage, furniture, and construction. But there is one quiet problem that can be gotten rid of at every step: friction. It accumulates between PVC particles, adheres to extruder parts, and even forms colloids in molten mixtures, damaging batches, wearing machines, and roughening sheet surfaces. This is where lubricants come in. These small but powerful additives reduce friction at every stage, keep production on track and ensure the appearance and performance of the final board meet requirements. Let us analyze the role of lubricants, how they are suitable for the manufacture of PVC foam sheets, and why reliable operation cannot be run without them.

What Are Lubricants, Anyway?

In PVC foam board making, PVC lubricants aren’t the same as the oil you put in a car—they’re specialized compounds, usually powders or small pellets, that tweak how PVC moves and interacts with equipment. The best part? They don’t change the board’s core traits, like how rigid or flexible it is. Instead, they focus on two big jobs:

First, internal lubricants (think glycerol monostearate, a common go-to) work inside the PVC mix. They slip between the long polymer chains of the resin, loosening things up so the molten material flows easier. Without them, the mix gets too thick, and the extruder has to work overtime—generating extra heat that can ruin the PVC.

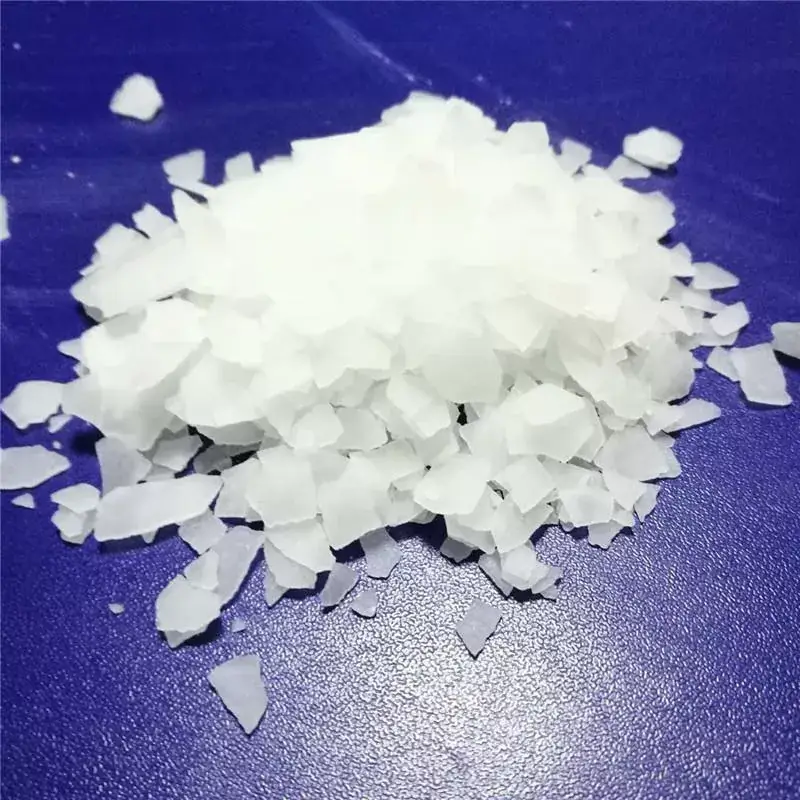

Then there are external lubricants, like polyethylene wax. These don’t mix much with PVC; instead, they migrate to the surface of the molten material, forming a thin, slippery layer between the plastic and the extruder’s metal parts (the barrel, screw, and die). This stops the PVC from sticking—no more gunk buildup on the die, no more worn-down screws, and no more boards with ugly “die lines” or rough edges.

Most factories use a blend of both. It’s like having two tools for one job: internal lubricants keep the mix flowing, external ones keep it from sticking to the machines.

Why Lubricants Are Non-Negotiable?

Skip the lubricants, and you’ll quickly run into headaches—ones that cost time, money, and good product. Here’s what they prevent:

1. Production shutdowns: Without lubrication, PVC can get so thick it clogs the extruder’s screw (called “screw slippage”) or sticks to the die, forming a buildup that stops the machine cold. Fixing that means taking the line down, cleaning parts, and tossing out the ruined batch—hours of lost work.

2. Burnt, discolored boards: When the extruder has to fight thick, sticky PVC, it generates extra heat—way above the 160–200°C sweet spot for PVC. That heat breaks down the resin, turning boards yellow or brown and making them brittle. Internal lubricants cut that friction, keeping temperatures steady and colors true.

3. Patchy foam structure: For a foam board to be strong and light, the tiny bubbles (from the AC blowing agent) need to be even. If PVC flows unevenly through the die, bubbles expand in weird spots—some too big, some too small, even empty gaps. Lubricants make the flow consistent, so every bubble forms right, and the board stays strong.

4. Rough, unusable surfaces: Sticky PVC leaves marks on the die—lines, bumps, or a chalky texture. For decorative boards (like wall panels or signage), that’s a dealbreaker. You’d either have to sand every board (more work!) or scrap them. External lubricants keep the surface smooth right out of the extruder.

5. Worn-out machines: Extruder screws and dies are expensive—replacing them can cost thousands. Friction grinds down metal over time, but external lubricants act as a buffer, extending the life of these parts by 20–30%.

How Lubricants Fit Into the Production Line?

PVC Lubricants don’t just get dumped in randomly—they’re part of the mix from the start, working with other additives to keep things moving:

1.The pre-mix stage: First, workers blend PVC resin with dry additives—calcium carbonate for strength, stabilizers to prevent heat damage, blowing agents for foam, and then the lubricants. A high-speed mixer spins everything together to make sure the lubricant is evenly spread. If it clumps, you’ll get spots where the PVC is too sticky or too runny—defects waiting to happen.

2. Compounding: The dry mix goes into a compounding machine, where heat (around 120–140°C) melts the PVC. This is where internal lubricants start working—loosening the polymer chains so the mix melts uniformly, no lumps or hot spots.

3. Extrusion (the critical step): The molten PVC moves to the extruder, and here’s where external lubricants shine. They coat the surface of the plastic, so it slides easily against the extruder’s barrel and screw—no sticking, no extra heat. Internal lubricants keep the mix fluid, so it flows evenly through the die (the tool that shapes the board).

4. Foaming and cooling: As the AC blowing agent creates bubbles, the smooth flow from lubricants ensures those bubbles are consistent. And since the PVC isn’t sticking to the die, the board’s surface is glossy and even. After extrusion, the board cools quickly—and the lubricants stay put, no leaching out or messing with how the board paints or prints later.

Why Lubricants Beat Other Fixes?

Some factories try to skip lubricants by tweaking the process—like cranking up the extruder temperature to thin the PVC. But that’s a bad trade: higher heat means burnt, brittle boards. Or they might use expensive coated extruder parts to reduce sticking—but those cost way more than lubricants and still don’t fix the internal friction problem.

Lubricants are better because they:

Keep PVC stable: They thin the mix without extra heat, so no degradation.

Save money: A bag of lubricant costs pennies compared to replacing a die or scrapping a batch.

Make every batch the same: Process tweaks (like temperature) are finicky—one small change and the next batch is off. Lubricants keep the flow consistent, so every board looks and performs like the last.

Play nice with other additives: They don’t react with stabilizers, plasticizers, or UV absorbers. You can mix them in without worrying about ruining the board’s strength or durability.

How to Pick the Right Lubricant?

Not all oils are suitable for all jobs-here are what factories are looking for:

Your extruder setup: If you are running a high-speed line (for mass production), PVC is subjected to greater shear forces, so you need stronger internal lubricants to keep it flowing. If your mold is older (rough surface), you need extra external lubricant to prevent sticking.

The type of board you are making: Rigid boards (such as signage) use less plasticizer (it already acts as a mild lubricant), so you need more internal lubricant. Flexible boards (such as floor mats) have more plasticizers, so you can reduce the lubricant.

Post-processing needs: If you want to print or paint circuit boards later, be careful of wax-based lubricants, which can leave a shiny film that repels ink. Fatty acid-based lubricants such as stearic acid are better suited for these jobs.

Regulations: If you're making food packaging boards (like inserts for takeout containers) or children's furniture, you'll need lubricants that meet safety standards, such as FDA-approved stearic acid. The EU's REACH regulation restricts certain waxes, so always check compliance if you're exporting.

What’s Next for Lubricants?

Like every part of PVC manufacturing, lubricants are getting greener and more efficient. Factories are starting to use bio-based options—made from plant oils or soy wax—instead of petroleum-based products. These are biodegradable and non-toxic, which fits with the push for more sustainable materials.

There are also new “high-efficiency” blends that work in smaller doses (0.3–1.5% instead of 2–3%)—same friction reduction, less raw material. And some companies are mixing lubricants with other additives: anti-static agents to keep dust off electronics packaging, or anti-microbial compounds to prevent mold on outdoor boards. These multi-tasking blends save time (no need to add multiple additives) and keep boards working better for longer.